Abraham Verghese on his new book The Covenant of Water, a sweeping family epic set in Kerala

[ad_1]

The Covenant of Water spans eight decades of a Kerala Christian family that suffers a strange affliction: at least one person dies by drowning in every generation.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images/ iStock

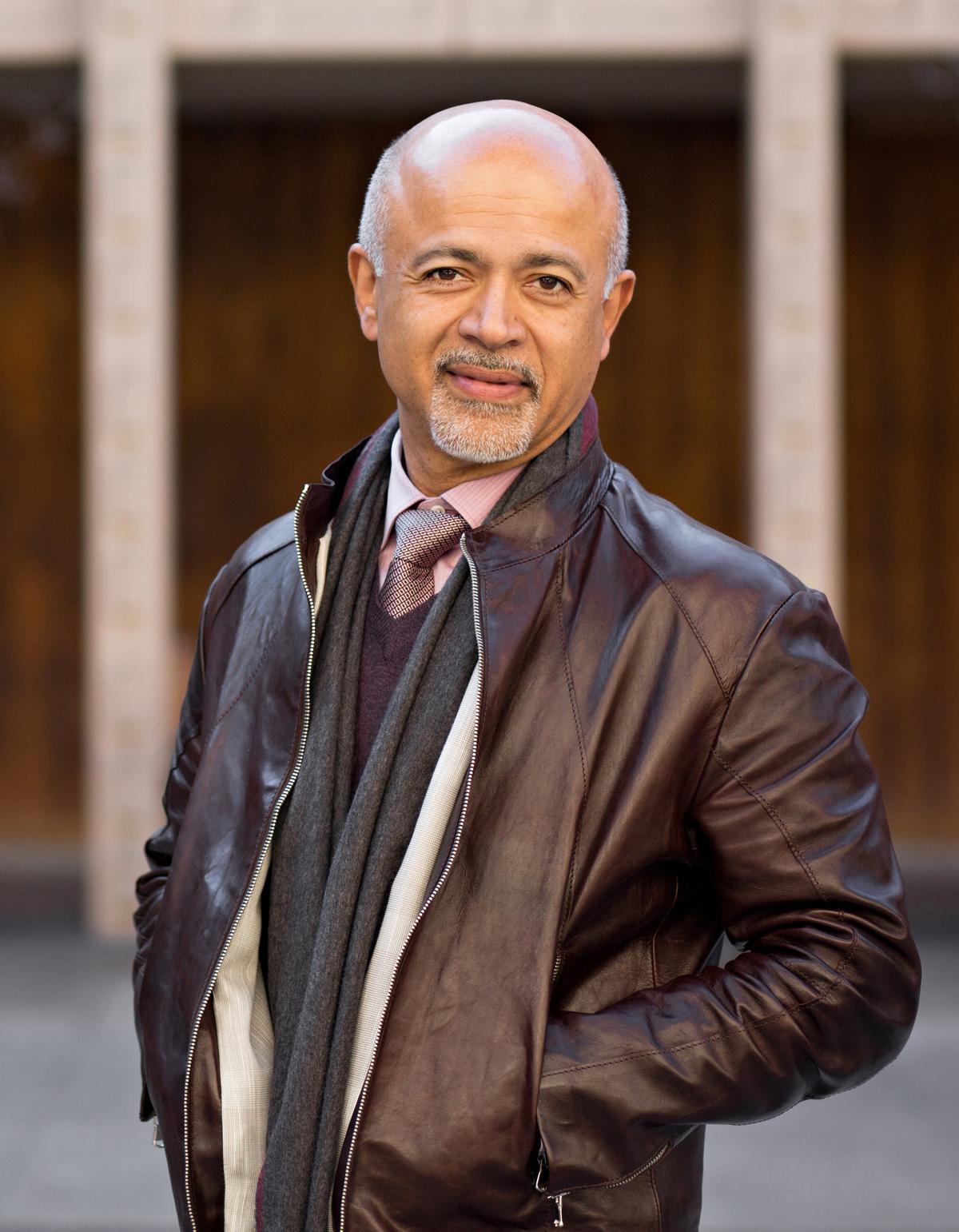

Abraham Verghese identifies himself primarily as a physician — medicine is his first love — and then as a writer. Born to Indian parents in Ethiopia and currently a Professor of Medicine at Stanford University, Dr. Verghese, 67, is known for his focus on healing in an era where technology often overwhelms the human side of medicine.

After two non-fiction books — My Own Country and The Tennis Partner — his debut fiction novel, Cutting for Stone (2009), a family saga that moves between Ethiopia and New York, became a bestseller. His latest, The Covenant of Water, is a sweeping epic about a Christian family in Kerala spanning eight decades.

In conversation with Abraham Verghese, author of The Covenant of Water

Medicine, history, culture, family and love form the themes of his work with some autobiographical elements. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Abraham Verghese

| Photo Credit:

Jason Henry

How did the idea for ‘The Covenant of Water’ come about?

I was searching for a locale for another novel, and came across this wonderful manuscript that my mother had written when she was in her 70s. She had been asked by my five-year-old niece, who was born in America, ‘Ammachi, what was it like when you were a little girl?’, and my mother was so taken with the question that she’d handwritten this 100-page manuscript with illustrations to give her granddaughter some sense of how completely different her life, two generations earlier, had been on another continent. Those stories were very familiar to me. I knew Kerala well from the time I’d spent summer vacations there, but they just sort of reminded me how rich that community was and gave me the confidence to try and set the new novel there.

At over 700 pages, it is a doorstopper, too long as some readers have observed.

I think modern tastes probably tend to run to something much shorter, slice-of-life things. I think everybody comes to it through their own taste, you can’t write entirely for market forces or the current taste. You have to write what you want to write and what you’re capable of, and you have to have the faith of an editor. I think the hardest thing is being objective about your own writing and I had an editor who was utterly confident that the length wasn’t the issue. The issue was he and I just making this a compelling story. It wasn’t about cutting it to make it the opposite of a doorstopper, which would be, I don’t know, a little paperweight on your desk.

Any essential truths the novel conveys for readers to take away?

I think all novels, if they’re successful, are conveying a truth. It was Camus who said something like ‘fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth’. If a novel resonates with a reader, it’s often very individual to them. It’s not like the author is hammering some generalised lesson for the reader to take away. The beauty of writing is, you as a writer provide the words and the readers provide their imagination.

I’d love it if the reader took away a sense of identifying with the characters and resonating with their lives and struggles, and maybe even feeling armed in some way with the lessons they may have learned from watching this other world play out.

You are fond of quoting that line of Camus’s. Why?

Because I increasingly hear my physician colleagues say ‘I’m a serious guy, I read only non-fiction’, as if fiction has nothing to offer. I tell them how slavery ended in America; it wasn’t the president or a politician but the book Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Similarly, in England, The Citadel (1937), a book describing medicine in a small mining town, captured public attention and that was the genesis of the National Health Service. For someone to feel that fiction is somehow made up and therefore not important is the opposite of what I believe.

Was the transition from non-fiction to fiction easy?

With fiction, you’re completely liberated. You can make it up, you can go back in time, you can go into people’s heads, you can go into the afterlife and come back but you have to work 10 times harder to keep the readers’ interest. With non-fiction, you really can’t invent, you can’t make up; you can rearrange, dramatise, but you can’t simply invent. I find them both challenging in their own way.

Going forward, would it be more of fiction from you?

I can’t rule out that I wouldn’t ever write another non-fiction, I well might. Having dabbled in fiction I think really that is where my next book will be.

I’m thinking more and more that I’ve set one novel in Ethiopia, the land of my birth, another in Kerala, the land of my ancestry, but I’ve lived the better part of my career in the U.S. So, the third novel, whatever it is, will be set somewhere in America but I don’t know in what time period or where.

Your thoughts on the recent trend of rewriting books to purge them of offensive or racist words?

It is a tricky thing. How far back do you go to correct the ills of humans against humans? I sort of object to censorship in any form unless it is truly inciting violence or something like that. I think we are seeing a disturbing trend, not just of political correctness in terms of removing objects from the past, but the other way around where we are warring about what our children are exposed to and banning books. If you don’t like it, don’t read it.

I’m an optimist, hoping that opinion will swing back and bring people to their senses.

The interviewer is a Bengaluru-based independent journalist and writer.

[ad_2]

Source link